Time Series Forecasting with Deep Learning and Embeddings: Time-series regression with a Random Forest and Feed-Forward Neural Network

published May 20, 2019

last updated January 17, 2021

In this article, we study a state-of-the-art predictive analytics pipeline for time-series structured data. In the parlance of time-series forecasting, the approach we take is known as “time-series regression.” We compare two models’ performance: a deep-learning (DL) feed-forward neural network with a random forest (RF) ML model. Structured data is also known as “tabular data” and represents the industry’s most common data format. Though it is well-known that deep learning has achieved significant breakthroughs for unstructured data, such as computer vision and NLP (Natural Language Processing), it is not as widely known that deep learning, with the use of embeddings, can provide significant predictive performance improvement for structured data.

Below, we walk through the Python code based on the Fastai library demonstrating how to set up a predictive analytics pipeline based on deep learning with embeddings. We utilize the Kaggle, Rossmann data set, discuss the deep-learning architecture, training, performance, and compare the performance to a machine learning tree-based model (Random Forest).

Examples of Other Timeseries Forecasting Use Cases

Forecasting problems include a broad set of use cases, such as the examples listed below, and many more.

- Equity price forecasting

- Sales forecasting

- Demand forecasting for manufacturing production

- Demand forecasting for inventory management

- Demand forecasting for infrastructure planning and utilizaiton

- Demand forecasting for workforce planning

Predictive Analytics and Forecasting

In the prediction and forecasting problem, the preprocessing stage of the pipeline consists of transformation of the independent variables including various aggregations. In the case of forecasting these also include time differences and lags. In ether case preprocessing produces a single row of data with potentially many independent variables corresponding to one or more dependent variables.

It is worth noting that a typical approach to forecasting is employment of ARIMA (Auto-Regressive Integrated Moving Average) models. Typically ARIMA models do not consider exogenous variables, the forecast is made purely with past values of the target variable or its transformation. In many forecast use cases, these models, including adjustments for trend and seasonality and multivariate time series, ARIMA models are very effective. In this case, our goal is to exploit a rich and complex set of exogenous variables for the purpose of achieving a better forecast so we take a predictive analytics approach based on random forest and deep-learning regression models.

The single row of independent variables is designed for predicting the dependent variable(s). The success of the overall prediction solution is dependent on properly engineering these predictive features (“feature engineering”). However, the predictive model and analytics pipeline is similar for prediction or forecasting. In the case of forecasting the index is a timeseries, and the prediction is a forward prediction in time.

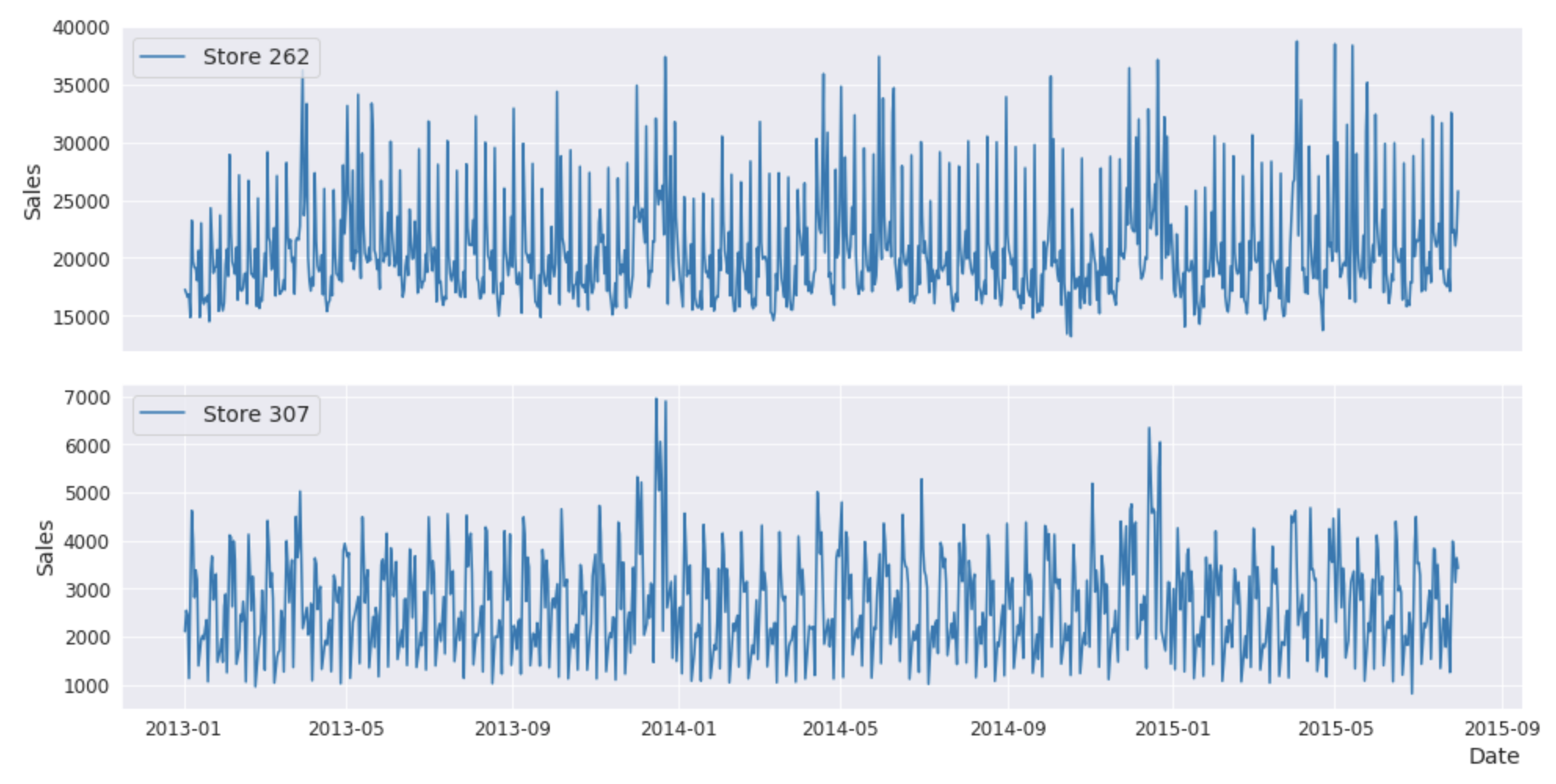

Rossmann Data Set

What is the the Rossmann data set? Rossmann is the largest drugstore in Germany and operates 3,000 drug stores in 7 European countries. In 2015 the store managers were tasked with predicting daily sales for up to 6 weeks in advance. Subsequently, Rossmann challenged Kaggle to predict 6 weeks of daily sales for 1,115 stores located across Germany, and thus released the data set to Kaggle. The data contains approximately 1 million rows with a size of 38 MB.

Why this data set? The Rossmann data set is chosen for the following reasons. A well understood data set with benchmarked performance and realistic complexity is preferred. For example, this is the case for several well-known data sets commonly used in the development of AI and ML models. Some examples include CIFAR for image processing, Wordnet for NLP, the Iris data set for prediction, handwritten digits for classification, and IMDb for sentiment classification. These tend to be excellent for exploring data algorithms because the data science community understands the data, the respective algorithms and performance, and there are numerous published examples with open source code.

Similarly, the Rossmann, Kaggle data set is becoming popular for exploring predictive analytics forecasting problems; case in point, it is referenced in the following use cases.

- Rossmann store sales competition

- Fastai introduction to Deep Learning for Tabular Data

- Stanford CS229, Final Projects based on Rossmann store sales

- Journal publications, Entity Embeddings of Categorical Variables

- Harvard CS109 Canvas Course Files

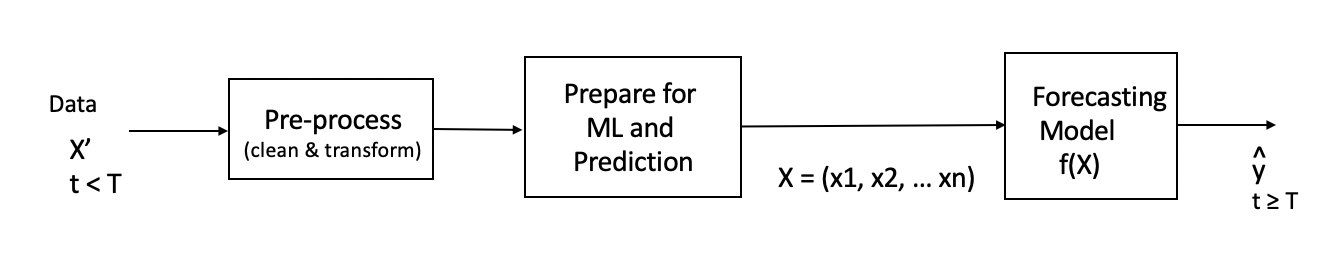

Data Processing and ML/AI Pipeline

The pipeline is common for both models studied in this post. The difference will be in one case an RF (Random Forest) model is used, and in the other a Deep Learning model is employed.

Figure 1. illustrates the data processing and ML/AI pipeline including loading the raw data, X’ (representing data prior to time T), preprocessing, preparing the data for machine learning and prediction, and forecasting of the future value ŷ for time t ≥ T. This article is primarily concerned with the 3rd step, the forecasting model and in particular entity embeddings within a deep-learning architecture. In order to appreciate the benefits of the deep-learning model, it is useful to compare it to an ensemble tree-based model, a Random Forest.

The coding begins with importing the fastai library (based on Fastai version 0.7). See installations instructions here Fastai 0.7. We also set a variable, PATH that points to the data set. The data is available from Kaggle, and for convenience, can be downloaded in one .tgz file from here.

from fastai.structured import *

from fastai.column_data import *

PATH='data/rossmann/'

Data Preprocessing

Though we do not discuss the code for the data preprocessing transformations in detail, it is essential to understand the data, including the preprocessing and ML preparation. However, for this article, the feature engineering is taken as a given.

We take the pre-processing and data preparation from the Kaggle 3rd place winners because they published their notebook and published a technical paper. The code is contained in the fastai lesson3-rossmann.ipynb Jupyter notebook. For convenience, a Jupyter notebook with only the preprocessing commands is available here. Input to the preprocessing is from the tables listed below. Additional information regarding these tables are further discussed on the Kaggle, Rossmann competition, data page

| Table | Columns |

| train.csv | Store, DayOfWeek, Date, Sales, Customers, Open, Promo, StateHoliday, SchoolHoliday |

| store.csv | Store, StoreType, Assortment, CompetitionDistance, CompetitionOpenSinceMonth, CompetitionOpenSinceYear, Promo2, Promo2SinceWeek, Promo2SinceYear, PromoInterval |

| store_states.csv | Store, State |

| state_names.csv | StateName, State |

| googletrends.csv | file,week,trend |

| weather.csv | file, Date , Max_TemperatureC , Mean_TemperatureC , Min_TemperatureC , Dew_PointC , MeanDew_PointC , Min_DewpointC , Max_Humidity , Mean_Humidity , Min_Humidity , Max_Sea_Level_PressurehPa , Mean_Sea_Level_PressurehPa , Min_Sea_Level_PressurehPa , Max_VisibilityKm , Mean_VisibilityKm , Min_VisibilitykM , Max_Wind_SpeedKm_h , Mean_Wind_SpeedKm_h , Max_Gust_SpeedKm_h , Precipitationmm , CloudCover , Events , WindDirDegrees |

| test.csv | Store, DayOfWeek, Date, Sales, Customers, Open, Promo, StateHoliday, SchoolHoliday |

First, the data files are read into a Pandas dataframe. The use of unique data sources can potentially have a good payoff for predictive performance. In this case, Kaggle competitors employed Google Trends to identify weeks and states correlated with Rossmann and weather information. This information is transformed into machine learning features during the ML preparation step followed by normalization (continuous variables) and numericalization of categorical variables. The processing employs typical methods for this type of data, for example, table joins, running averages, time until next event, and time since the last event. The outputs of the preprocessing and preparation section are saved in the “joined” and “joined_test” files in “feather” format, which are then loaded into the Jupyter notebook for the next step of processing (“Prepare for ML and Prediction”).

joined = pd.read_feather(f'{PATH}/joined')

joined_test = pd.read_feather(f'{PATH}joined_test')

The columns (i.e., variables) of the joined table include Sales the dependent variable and all other variables (independent variables). The independent variables within each row are processed from their original form in X’ (as described in the previous paragraph) so that one row of independent variables is intended to predict the corresponding dependent variable, Sales (in the same row).

Prepare for Machine Learning

The next stage of the pipeline begins with the joined tabular data from the previous section. Machine learning algorithms perform better when the continuous value inputs are normalized and require the categorical values to be numericalized. Furthermore, artificial neural networks require the inputs to be zero mean with standard deviation of 1. Both of these steps are performed below.

Categorical and Continuous Variables

The categorical variables and numerical variables are listed in the cat_vars list and contin_vars list. These variables are selected from the joined table as features for machine learning and prediction.

cat_vars = ['Store', 'DayOfWeek', 'Year', 'Month', 'Day', 'StateHoliday', 'CompetitionMonthsOpen',

'Promo2Weeks', 'StoreType', 'Assortment', 'PromoInterval', 'CompetitionOpenSinceYear', 'Promo2SinceYear',

'State', 'Week', 'Events', 'Promo_fw', 'Promo_bw', 'StateHoliday_fw', 'StateHoliday_bw',

'SchoolHoliday_fw', 'SchoolHoliday_bw']

contin_vars = ['CompetitionDistance', 'Max_TemperatureC', 'Mean_TemperatureC', 'Min_TemperatureC',

'Max_Humidity', 'Mean_Humidity', 'Min_Humidity', 'Max_Wind_SpeedKm_h',

'Mean_Wind_SpeedKm_h', 'CloudCover', 'trend', 'trend_DE',

'AfterStateHoliday', 'BeforeStateHoliday', 'Promo', 'SchoolHoliday']

n = len(joined); n

Training, Validation and Test Set

Next, the training and validation sets are created, with use of the fastai proc_df() function, which performs the following functions.

- The dependent variable is put in into an array, y and independent variables are put into the dataframe, df.

- Continuous variables are normalized (zero mean and standard deviation = 1), and categorical variables are enumerated.

- Continuous variable missing values are filled with the median, and categorical id of 0 is reserved for categorical variable missing values.

- The dictionary nas is a mapping of the N/A’s and the associated median.

- mapper is a DataFrameMapper, which stores the mean and standard deviation of the continuous variables and can be used for scaling during test time.

The val_idx variable are indexes identifying the part of df (training set) to be used for validation. In this forecasting problem, the validation indexes correspond to the same time frame (different year) as in the test set (from joined_test) and in this case the test set time frames are defined by Kaggle.

df, y, nas, mapper = proc_df(joined_samp, 'Sales', do_scale=True)

yl = np.log(y)

joined_test = joined_test.set_index("Date")

df_test, _, nas, mapper = proc_df(joined_test, 'Sales', do_scale=True, skip_flds=['Id'],

mapper=mapper, na_dict=nas)

val_idx = np.flatnonzero(

(df.index<=datetime.datetime(2014,9,17)) & (df.index>=datetime.datetime(2014,8,1)))

Optimization Function and Log y

One additional transformation is necessary prior to machine learning. The optimization function for evaluation of results is RMSPE (Root Mean Square Percentage Error). The Kaggle submissions are evaluated on the Normalized Root Mean Squared Percent Error (RMSPE), calculated as follows:

\[\enspace\enspace EQN-1 \hspace{3em} RMSPE = \sqrt{\frac{1}{n}\sum_{k=1}^n \left( \frac{y_i - ŷ_i}{y_i} \right) }\]This metric is suitable when predicting values across a large range of orders of magnitudes, such as Sales. It avoids penalizing large differences in prediction when both the predicted and the true number are large: for example, predicting 5 when the true value is 50 is penalized more than predicting 500 when the true value is 545.

The RMSPE metric is not directly available from machine learning libraries. For example, it is not available form fastai, PyTorch, or Sklearn. The optimization function typically available for regressor functions is RMSE (Root Mean Square Error). Therefore, it is typical to use log properties as follows.

For example, for percent error $\sum_i{ \frac{ŷ_i } {y_i} }$ we use the property $ln(\frac{a}{b}) = ln(a) - ln(b)$. Percent error is given by

\[\enspace\enspace EQN-2 \hspace{3em} \sum_i{ ln \left( \frac{ŷ_i} {y_i} \right) } = \sum_i{\left(ln(ŷ_i) - ln(y_i) \right)}\]The implication is that when we take the log of the percent error, then we get RMSPE for free. That is, taking the inverse log $exp^{log(RMSPE)}$ we get the RMSPE, the desired metric.

For convenience, we define the following functions.

def inv_y(a): return np.exp(a)

def exp_rmspe(y_pred, targ):

targ = inv_y(targ)

pct_var = (targ - inv_y(y_pred))/targ

return math.sqrt((pct_var**2).mean())

max_log_y = np.max(yl)

y_range = (0, max_log_y*1.2)

Tree based model (Random Forest)

At this point, the data is ready for machine learning. Training a Random Forest ML model is useful to establish a performance baseline, and one consistent with the published performance benchmark. The dependent variable is the log of Sales (yl) and the independent variables are in the df dataframe. The indexes in val_idx are used to split between training and validation. A Random Forest regressor with 40 estimators, 2 samples per leaf yields an RMSPE score of 0.1086. It is worthwhile noting that the tree models do not require one-hot encoding of categorical values, because they operate on the concept of partitioning the decision space. Also, at this point the categorical variables are numerical values so the model can operate directly on the df dataframe.

from sklearn.ensemble import RandomForestRegressor

((val,trn), (y_val,y_trn)) = split_by_idx(val_idx, df.values, yl)

mrf = RandomForestRegressor(n_estimators=40, max_features=0.99, min_samples_leaf=2,

n_jobs=-1, oob_score=True)

mrf.fit(trn, y_trn);

preds = mrf.predict(val)

mrf.score(trn, y_trn), mrf.score(val, y_val), mrf.oob_score_, exp_rmspe(preds, y_val)

(0.9821234961372078,

0.9316993731280493,

0.9241039979971587,

0.10863755294456862)

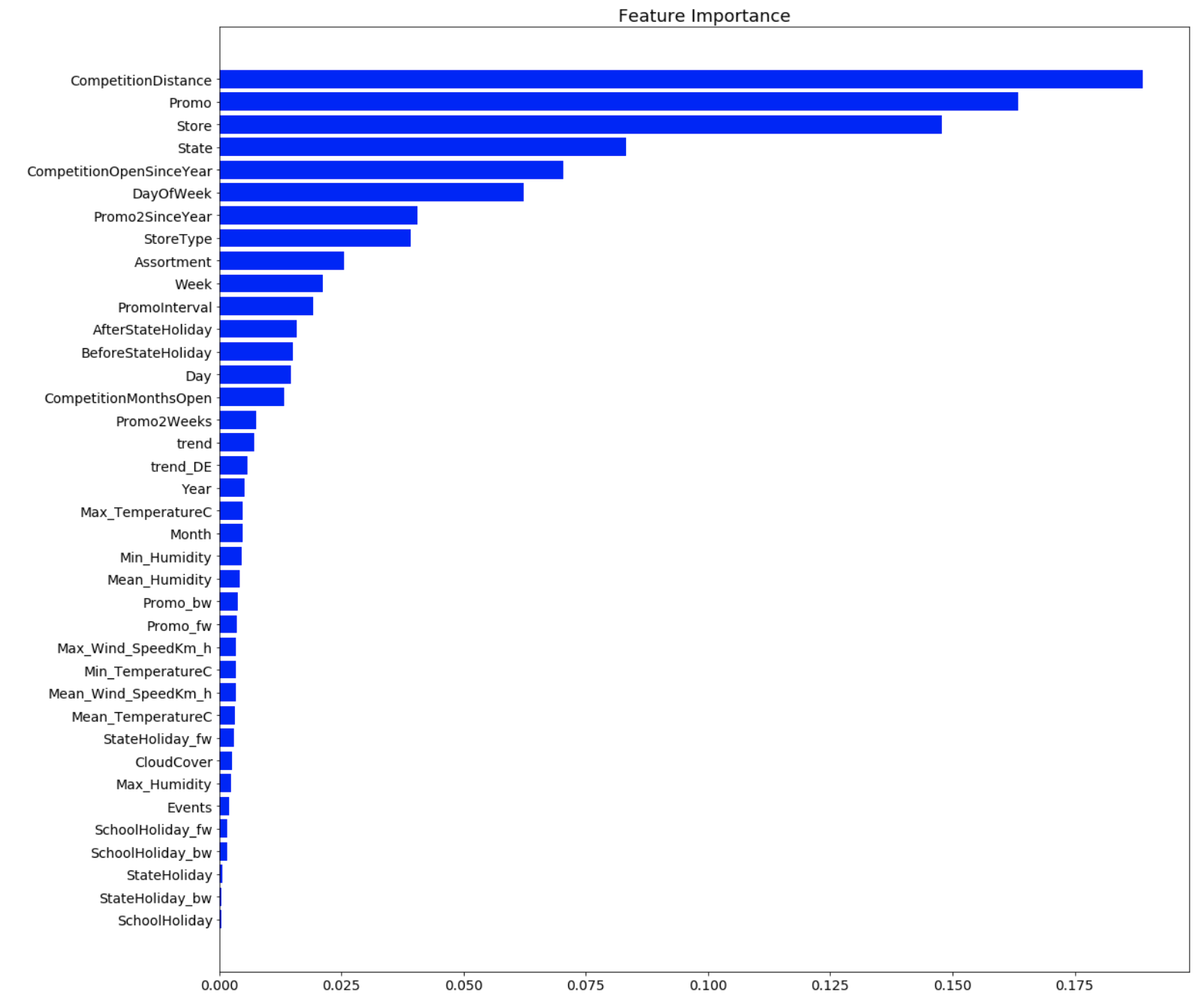

Figure 2 illustrates the feature importance corresponding to the RF model. There is likely some improvement from feature reduction through a technique such as PCA. At this point our goal is to reproduce the results from fastai and create a model that can reused for other problems so we will forego this step at this time. It is also known from experience that RF models tend to perform well despite the presence of a modest amount of multi-collinearity amongst the ML features.

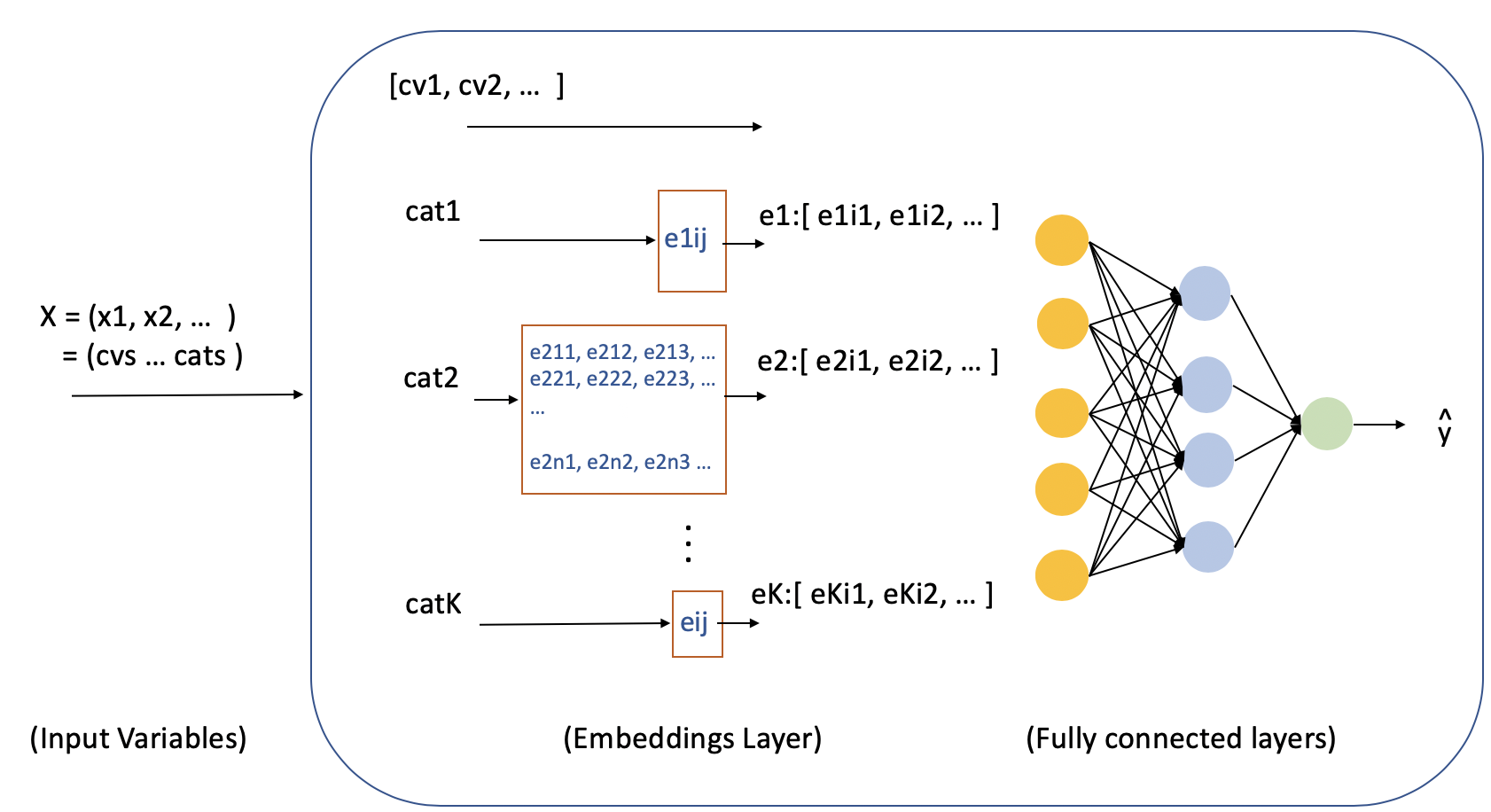

Deep Learning with Embeddings

The deep learning (DL) with Embeddings architecture is illustrated in Figure 3. The DL model receives as input the feature variables generated from the previous stage of processing and is comprised of continuous and categorical variables, (cvs … cats…). The architecture is based on the Fastai embeddings for structured data architecture. The first layer is an embeddings layer followed by two fully connected layers, and then the output layer.

Deep Learning Model

The deep learning model is defined with the Fastai ColumnarModelData() class. It receives as input the PATH, validation indexes, Numpy array of independent variables (df.values), batch size, and test set (df_test). Next, a learner object is created with md.get_learner(). The learner receives as input the size (“cardinality”) of each categorical variable.

md = ColumnarModelData.from_data_frame(PATH, val_idx, df, yl.astype(np.float32), cat_flds=cat_vars, bs=128,

test_df=df_test)

cat_sz = [(c, len(joined_samp[c].cat.categories)+1) for c in cat_vars]

emb_szs = [(c, min(50, (c+1)//2)) for _,c in cat_sz]

# Inputs to the learner:

# No. of continuous variables = total Variables - Categoricals.

number: Sales

# Categorical variable dropouts is set to .04

# Output of the last linear layer, is 1, for predicting single output value

# Activations in first and second linear layers ... [1000,500]

# Dropout in first and second linear layers ... [.001,0.1]

m = md.get_learner(emb_szs, len(df.columns)-len(cat_vars),

0.04, 1, [1000,500], [0.001,0.01], y_range=y_range)

lr = 1e-3

As illustrated in the diagram, there is an embeddings table for each categorical value. The embeddings are setup and work as follows:

- By rule of thumb, the width of each table is sized proportionally to the cardinality of the corresponding categorical variable (cardinality divided by 2 plus 1) up to a width of 50. The value 0 is reserved for unknown.

- The number of rows is the cardinality of the categorical variable.

- Each categorical variable serves as a lookup to the i-th row of values (ek_ij) corresponding to the k-th categorical variable.

- The output from each table, embeddings row, are effectively concatenated with the continuous values to form the input into the fully connected layers.

- The embedding values (ek_ij) are optimized as part of the deep-learning model stochastic gradient descent training.

Below are listed the width’s, cat_sz, for each embeddings table.

The first fully connected layer is set to 1000 activations with ReLU non-linear functions, and the second fully connected layer is set to 500 activations (also ReLU), and 1 sigmoid output. The output range is defined with y-range.

cat_sz = [(c, len(joined_samp[c].cat.categories)+1) for c in cat_vars]

cat_sz

[('Store', 1116),

('DayOfWeek', 8),

('Year', 4),

('Month', 13),

('Day', 32),

('StateHoliday', 3),

('CompetitionMonthsOpen', 26),

('Promo2Weeks', 27),

('StoreType', 5),

('Assortment', 4),

('PromoInterval', 4),

('CompetitionOpenSinceYear', 24),

('Promo2SinceYear', 9),

('State', 13),

('Week', 53),

('Events', 22),

('Promo_fw', 7),

('Promo_bw', 7),

('StateHoliday_fw', 4),

('StateHoliday_bw', 4),

('SchoolHoliday_fw', 9),

('SchoolHoliday_bw', 9)]

What’s the big idea with Embeddings?

The performance gains of deep Learning are primarily attributed to entity embeddings. Entity embeddings are a low-dimensional representation of the high dimensional space of categorical variables. Consider, for example, the following intuition. A common technique for representing a categorical variable is one-hot encoding. For the case of a movie title one-hot encoding quickly results in a sparse representation consisting of a row with thousands of columns in width with one non-zero element representing one movie title.

In contrast, an entity embedding represents the relationship between movies with a low-dimension vector, such as, for example, genre. In this case, a movie title is encoded with a low-dimensional vector representing genres: western, action, drama, sci-fi, cinematography, etc. When they are input to a machine learning algorithm, these low dimension entity embeddings representations enable the algorithm to exploit relationships between categorical elements.

Fit

With the model defined, it is time to fit. The learning rate is set to 1e-3. Though not demonstrated here, it is useful to mention that the Fastai library includes the lr_find() method to find an optimal learning rate based on the paper Cyclical Learning Rates for Training Neural Networks.

m.fit(lr, 1, metrics=[exp_rmspe])

epoch trn_loss val_loss exp_rmspe

0 0.013699 0.013854 0.116042

The model is trained with several epochs at a constant learning rate.

m.fit(lr, 3, metrics=[exp_rmspe])

epoch trn_loss val_loss exp_rmspe

0 0.011076 0.015949 0.113352

1 0.009257 0.012345 0.10875

2 0.008702 0.011414 0.102238

Next, the cycle_len =1 parameter enables SGDR with restarts, whereby the learning rate is decreased with Cosine Anealing profile over a cycle_len measured in Epochs. Following a cycle the learning rate is returned to lr to begin another cycle.

m.fit(lr, 5, metrics=[exp_rmspe], cycle_len=1)

epoch trn_loss val_loss exp_rmspe

0 0.007108 0.010651 0.098073

1 0.00664 0.010301 0.096721

2 0.007111 0.010438 0.096768

3 0.006871 0.010481 0.096761

4 0.006245 0.010313 0.096277

After 5 epochs we obtain an RMSPE of 0.0963 representing approximately 11% improvement over the Random Forest. The Random Forest, though receives as input the numericalized categories, does not employ embeddings.

Test

On the test data we obtain an RMSPE of 0.0998.

md = ColumnarModelData.from_data_frame(PATH, val_idx, df, yl.astype(np.float32), cat_flds=cat_vars, bs=128,

test_df=df_test)

m = md.get_learner(emb_szs, len(df.columns)-len(cat_vars),

0.04, 1, [1000,500], [0.001,0.01], y_range=y_range)

m.load('val0')

x,y=m.predict_with_targs()

print(exp_rmspe(x,y))

pred_test=m.predict(True)

pred_test = np.exp(pred_test)

pred_test

0.09979241514057972

Predict

Following training and test is prediction (forecasting in this case) when new data comes in. Below, are listed the necessary steps, including loading the saved model and creating new forecasts. Additionally, though not shown below, is to preprocess and prepare the data with an identical pipeline as that used for training. For convenience, to illustrate the mechanics of prediction, we predict based on the test data (already preprocessed and prepared for ML).

md = ColumnarModelData.from_data_frame(PATH, val_idx, df, yl.astype(np.float32), cat_flds=cat_vars, bs=128,

test_df=df_test)

m = md.get_learner(emb_szs, len(df.columns)-len(cat_vars),

0.04, 1, [1000,500], [0.001,0.01], y_range=y_range)

m.load('val0')

# columnar data set

cds = ColumnarDataset.from_data_frame(df_test,cat_vars)

# data loader

dl = DataLoader(cds,batch_size=128)

# log predictions

predictions = m.predict_dl(dl)

# exp (log predictions) = predictions

predictions=np.exp(predictions)

predictions

array([[ 4475.422 ],

[ 7242.9165],

[ 9095.177 ],

[ 7343.125 ],

[ 7703.5986],

[ 5933.637 ],

[ 7425.5747],

[ 8448.557 ],

...,

Summary and Conclusions

In summary, two time-series regression models (ML and DL) for forecasting future grocery store sales were compared. The deep learning with embeddings model produces world-class predictive performance on the Rossmann data set. The model achieves a significant improvement as compared to a Random Forest (RF) model, the next best model as reported in Entity Embeddings of Categorical Variables. The RSMSPE performance of the two models are listed in Table 1, below, where the Deep Learning model achieves a an 8% improvement in RSMPE score as compared to the RF model.

| Model | RMSPE |

| Random Forest | 0.1086 |

| Deep Learning | 0.0998 |

Though it is significantly more complex than the RF model, the training time is approximately the same on a basic GPU vs. Random Forest trained on a CPU. The key differentiating method for achieving the performance gain is the use of entity embeddings. Entity embeddings are a low-dimensional representation of the high dimensional space of categorical variables and enable machine learning algorithms to exploit relationships between categorical items.

| Characteristic | Description |

| Machine Learning Pipeline | - Data preprocessing - Prepare data for ML and Prediction - Machine Learning and Prediction |

| Architecture | Deep learning with embeddings - Embeddings layer - 2 Fully connected layers, 1000 and 500 ReLU activations - Output layer 1 sigmoid activation |

| Data Set | - Rossmann, Kaggle data set - preprocessing steps taken from 3rd place winner - 844,438 raining rows, 22 categorical features, 16 continuous features |

| Training | - Paperspace P4000 virtual desktop: NVIDIA P4000, 8 GB GPU, 1791 CUDA Cores, and 30 GB, Intel Xeon E5-2623 v4 CPU - ~10 minutes - SGDR with restarts and cosine annealing |